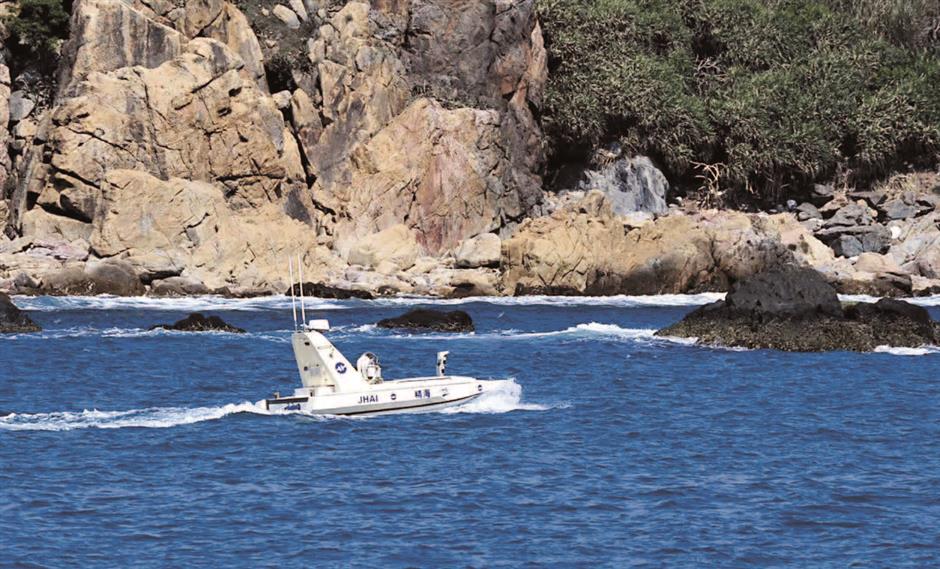

An unmanned vessel developed by Shanghai scientist Peng Yan is tested at sea in this file photo. Peng is a researcher and inventor who is helping pave the way for more women to become involved in a male-dominated bastion.

A Shanghai inventor of unmanned vessels is not only distinguished for her work but also distinctive because she is a woman in a male-dominated scientific community.

Peng Yan, 36, is director of Shanghai University’s Research Institute of Unmanned Surface Vehicles Engineering. Her work has led to inventions used to monitor safety conditions in the Huangpu River, detect water quality after oil spills in the East China Sea and explore what’s above and under the ice in Antarctica.

The British scientific journal “Nature,” on its website on May 2, published an article entitled “Close the Gender Gap in Chinese Science.” It noted that only about one-quarter of China’s scientific workforce last year and just 6 percent of the members of the Chinese Academy of Science were women.

But Peng’s team is starting to break that mold. Nine of its 30 members are women, aged from 23 to 48.

Generally, there is some movement toward more diversity in science occupations, Peng said, but in too many cases, women are still underrepresented.

There are social and cultural reasons for the disparity. Girls are generally brought up to believe that hands-on, practical activities are not for them. They are expected to pay attention more to family than workplace. For female scientists, there are additional challenges.

“We work every day,” she said. “We don’t necessarily have weekends or holidays off. When there is mission, we just wake up at midnight and get to work in the school’s lab.”

A spacious venue on the campus serves as workshop and warehouse for the team.

“In most cases, research results can’t be applied because no one can turn a blueprint into reality,” she said. “So, we have to resolve it by ourselves. We assemble the ships by ourselves. When the vessels are tested, we need to be on the scene, exposed to scorching sunshine and strong waves.”

Peng doesn’t think it takes a man to do the job effectively.

“What really matters is stamina and whether a person can endure the hardships,” she said.

When Peng was pregnant, she didn’t hesitate to rush to the seaside to work, if called upon. After her son was born, she simply took him with her everywhere.

“He’s 5-and-1/2 years old now, and he loves staying in my office when I am at work,” Peng said. “He tells me he wants to do the same work as me when he grows up.”

Peng said she is grateful for support she gets from her family.

“I don’t have time to go out shopping, but, luckily, we have the Internet for that,” she said.

Women scientists are often tagged as eccentric, but Peng and her female colleagues are pretty normal people. They wear make-up and one-piece dresses. They are talkative and easy going.

“We are women in a new age,” she said.

Peng represented her team in receiving a visit from Shanghai Party Secretary Li Qiang on a tour of the university in May. Another female member, Xie Shaorong, 46, was cited among the top 20 scientists and professionals during the Shanghai Science Festival and got to walk up a red carpet.

“It made me feel like a superstar,” Xie said. “I really felt that as scientists, we are respected.”

Peng started thinking about development of an unmanned vessel in 2005. Together with Xie, who had a background in robot research, they helped found the research team in 2009.

A year later, they unveiled a prototype unmanned vessel that was used to monitor underwater safety of the Huangpu River during the 2010 Shanghai World Expo.

It wasn’t an easy task. The river is relatively shallow as it passes through the city, and it is choked with silt. The unmanned vessel is equipped with advanced sonar and precise sensors.

“It took us a long time to study underwater conditions and carry out tests,” said Shao Wenyun, 48, another female member of the team. “But it was important to get it right way, by trial and error. Theoretically, aluminum is rust-proof, but practically, it did rust when we used it to build the vessel. So, we had to test again and again to find the right solution.”

The unmanned vessels have been upgraded to the ninth generation. They can move fast, sensor precisely and evade obstacles — the three most important factors to ensure safety, Peng said.

Peng’s team also designed China’s first unmanned surface vessel to accompany the icebreaker Xuelong to Antarctica’s Ross Sea in 2014.

“Previously, what was below the ice was unknown,” said Xie. “So, large vessels just drifted above deep sea to avoid running onto rocks. The unmanned vessel helped locating safe anchorage for the Xuelong, which saved the exploration project 500,000 (US$78,24 4) to 600,000 yuan of oil every day.”

It also mapped what’s below a 12-square-kilometer stretch of sea and made the world’s first nautical chart of the Ross Sea.

Earlier this year, the oil carrier Sanchi, carrying 136,000 tons of light crude from Iran, collided with a Hong Kong-registered bulk freighter about 300 kilometers east of the Yangtze River estuary and has been burning ever since.

Large amounts of oil spread across the sea. An unmanned vessel was deployed to detect water quality and collect samples for analysis.

Next up on Peng agenda is work focusing on emerging industries, such as artificial intelligence, to render their unmanned vessels “smarter” and to adopt environmentally friendly fuels and materials.