Childhood memories of Chinese literati

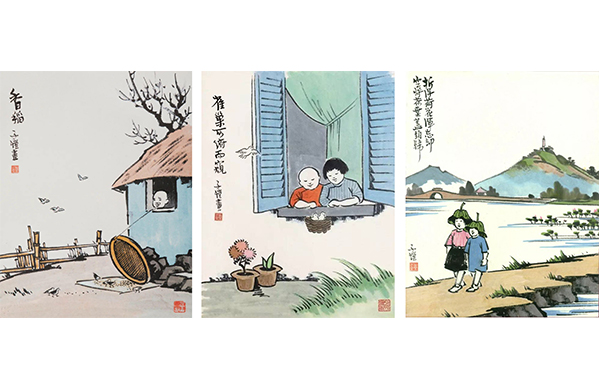

FILE PHOTOS: Paintings by the famous artist Feng Zikai (1898–1975) offer glimpses of childhood in China.

“Memories of childhood were the dreams that stayed with you after you woke,” an unnamed netizen wrote on a social media platform. Childhood experiences affect our behaviors and personalities well into adulthood, even if these connections are subconscious. Children yearn to become adults, while adults are often overwhelmed with longing for the innocent days of their early childhood. Through the memories of celebrated authors, readers can gather inklings of how they were molded by their childhood experiences.

Wang Zengqi

Hailed as a “humanistic, vernacular, and lyrical poet,” Wang Zengqi’s (1920–1997) writing style breaks the boundaries that separate essays, poetry, and fiction-writing. His language is infused with the poetic elegance and culture of Chinese literati. In his essay “The Garden,” Wang recalled his family’s garden, which made his childhood joyous and carefree:

“I was awakened by birdsong daily. I heard birds chirping in my dreams until I woke up. I grew familiar to some of the bird calls, as I heard them almost every day. These calls seemed to come from a certain branch.

I cried for a bird once. It was a sparrow or a laihua [a bird which looks similar to a sparrow]. I can’t remember who gave it to me, but the bird filled me with great joy. From my father’s spare cages made of thin bamboo strips, I picked the finest one and matched it with the best food container...I spent half a day decorating this cage. The next day, I woke up very early, and hung the cage under the wisteria trellis. The wisterias were blooming—it was the best place in the garden. After everything was done, I admired the bird in its exquisite cage for a long time before going to school. After school, I came back in a hurry, and went to see my bird with books still in my hands. The cage was on the ground, broken into pieces, and yet there was still half a bowl of water in the food container. ‘Where is my bird? Where is my bird?’ My father was grafting his flowering peach trees. Hearing my voice, he walked over and took a look at the cage. ‘The cage was placed too low. Now the bird is in the belly of your uncle’s cat,’ he said. I burst into tears. ‘Come on. You’re grown up now.’ My father soothed me as he led me back to the house.”

Ji Xianlin

Ji Xianlin (1911–2009), dubbed by many as the “master of Chinese culture,” was a linguist, paleographer, historian, writer, and an Indologist honored by both Chinese and Indian governments. In his biography, Ji recalled his primary school life in Jinan, Shandong Province:

“Did I ‘behave?’ I guess not. We nicknamed our abacus teacher ‘Shao Qianr,’ which meant cicada in the Jinan dialect, for he had bulging eyeballs. ‘Shao Qianr’ was rude to us. Anyone who made a mistake during abacus calculations would be punished with a ferule. Mistakes were unavoidable, so we were feruled many times. ‘Why not kick him out of school?’ a student muttered. His suggestion was warmly received. We, a group of teens, were going to ‘revolt.’ Our plan was to flip his table over while he was giving a lesson, run out of the classroom, and hide behind the rockery. We believed it was a canny move, which would humiliate ‘Shao Qianr’ and force him to leave. Unfortunately, we didn’t expect ‘traitors’ among us, even though there were only a few. They refused to leave the classroom in order to flatter ‘Shao Qianr.’ This treachery fed our teacher’s arrogance tremendously. With ‘supporters’ backing him up, his authority inflated. The arrogant ‘rebels,’ including me, were punished severely by strokes of the ferule on our palms, which made our hands swell up like steamed buns.”

Bing Xin

Xie Wanying (1900–1999), better known by her pen name Bing Xin, was one of China’s most prolific female writers of the 20th century. Bing Xin’s father served in the navy when she was young. She was deeply influenced by her father’s military life, as portrayed in her essay “My Childhood.”

“When I was young, the environment turned me into a ‘wild child’—I was not girly at all. My family always lived close to a naval camp or a naval academy. There were few girls my age. I never played with dolls or learned needlework; neither did I wear any makeup, bright colors, or flowers in my hair. Conversely, because my mother was often sick and the house was too quiet, I followed my father all day, even when he was working or participating in various activities, and I gained experience that even most men couldn’t get. For convenience, I often wore men’s clothing and military uniforms.

When my father was working, his colleagues often showed me around. I have been to the flag platform, barbette, naval dock, arms depot, and the Temple of the Dragon King [in Chinese mythology, the Dragon King is a deity who controls the oceans, all weather, and sea creatures]. I talked with gunsmiths, disabled guards of the arms depot, sailors, and military officers. Most of them were from Shandong Province. They were kind and simple. They told me many novel and tragic stories that happened on the sea. Sometimes I met farmers and fishermen, who talked about the minutiae of their quotidian existence. I hardly met any women, except for my mother and the wives of my father’s colleagues.

My childhood experiences had enduring effects and shaped my personality. It can be found in my serious attitude towards life. I like everything to be neat, tidy, and disciplined. I am afraid of slovenliness and slackness.

Furthermore, I enjoy wide open spaces and solitude. Loneliness never bothered me. Many times, I wanted nothing more than to merge into the vast emptiness. Going into the wild feels like returning to my hometown. I don’t like living in the city and socializing, neither do I fit into the urban lifestyle.

I don’t like to wear bright colors. My favorite colors are black, blue, gray, and white. Sometimes, my mother forced me to put on brightly colored clothes, which made me feel shy and uncomfortable. I couldn’t wait to take them off.

I prefer to approach others in a straightforward, frank, and natural way. It’s hard for me to do things I don’t want to do, to see people I don’t want to see, and to eat something that I don’t want to eat. My mother labeled this trait as a type of self-indulgence, which she believed prevented me from developing a ‘great personality.’

Lastly, I have deep respect for people who serve in the army. In my eyes, they symbolize nobility, courage, and discipline. I’m also interested in everything related to the military.

Eileen Chang

Although born into an aristocratic family as a descendant of the 19th-century leading Chinese statesman Li Hongzhang (1823–1901), the eminent female writer Eileen Chang (1920–1995) didn’t have a happy childhood. Her father was addicted to opium and divorced her mother. This might explain why her literary maturity was said to be far beyond her age. A section of Chang’s autobiographical essay “The Guileless Words of a Child” hints at Chang’s potential maturity even when she was just a girl:

“One of my earliest memories was of my mom standing in front of a mirror, pinning an emerald brooch onto her green short coat. I stood beside her, looking up at her admiringly. I could hardly wait to grow up. I said: ‘I’m going to have the S-shaped curly haircut [a vintage hairstyle popular in Shanghai in the 1920s and 1930s] at age 8, wear high-heeled shoes at age 10, eat zongzi, tangyuan [traditional Chinese desserts made of sticky rice], and all the other hard-to-digest foods at age 16.’ The more impatient I became, the more I felt the clock ticking slowly. Days of my childhood crawled by, warm and sluggish. They were like sunshine on the pink fleece lining of old cotton-padded shoes.

Sometimes the clock seemed to tick so fast—which I also hated—that I outgrew my newly-tailored Western-style dress, which was made of green brocade, even before it was ready for me to wear. This dress became my lifelong regret. I got depressed whenever I thought about it.

For a period of time, I lived with my stepmother. I had to wear her old clothes. There was a dark-red thin padded gown that I will never forget. Most days I had no choice but to wear this gown, which had the color of ground beef. Wearing this gown felt like having old sores all over my body, scars that refused to go away even when winter passed—I felt a deep sense of shame and repulsion. In middle school, I was unhappy and seldom made friends, mostly because I felt dowdy and ugly.”

Whether or not these authors’ childhoods were typical, or remembered in a positive light as a state of freedom and innocence, their respective upbringings shaped their writings later in life. These memoirs have preserved childhood indefinitely, capturing snapshots of China through different eras and the young personalities of great figures in Chinese literature.