Shanghai Daily news

The Pujiang Hotel in the northern area of the Bund was

the first major hotel to be built in Shanghai when it was known as the Astor

House Hotel.(Photo: Shanghai Daily)

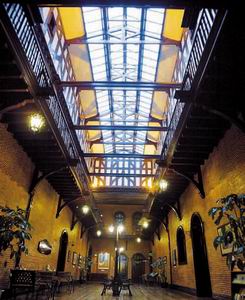

A look at part of the hotelí»s interior. (Photo:

Shanghai Daily)

Shanghai's first-ever hotel was a sea captain's hostel that became a legend -

over-the-top luxury, mod cons and celebrities. Tina Kanagaratnam investigates

the history of the Astor House Hotel, and finds connections to everything from

Shanghai's first taxi to the world's most famous ballerina.

From the Peace

Hotel to the Grand Hyatt, Shanghai's landscape has been defined by hotels - so

it is a little strange to imagine a Shanghai without one. But that was the case

until 1846, when the city's first hotel opened.

It was just four years after

the Treaty of Nanjing, the catalyst for the creation of the British Settlement,

and interest in this new treaty port was high. Called the Richard Hotel, after

the American sea captain of the same name who was its first owner, the hotel was

initially targeted at the seafaring clientele that made up the bulk of travelers

to 19th century Shanghai.

Information on the Richard Hotel is scarce, but one

contemporary account describes corridors and floors whose color and design

echoed those on ships. A string of sea captains followed the original as

managers of the hotel, but perhaps life on land did not suit them, for by 1860,

the hotel was sold to Henry Smith, who changed the name to the Astor House

Hotel.

Why the name Astor House? Perhaps it was an attempt to be associated

with Astor House in New York, built in 1836 by John Jacob Astor, the richest man

in America. Astor House, which was located on Broadway, was the city's first

luxury hotel, with amenities that included running water in every room.

The

Shanghai Astor House appears to have no connection to the New York one, but then

again, maybe it did: Astor was no stranger to China, having made a fortune in

China by selling Turkish opium and bringing back tea.

Perhaps it was the

American connection, perhaps it was the intimation of luxury or perhaps there

was nowhere else to stay in Shanghai - but whatever the reason, this was where

(then former) US President Ulysses S. Grant stayed when he visited Shanghai in

1879.

There is little information on the original location of Richard Hotel,

but it is very likely that it was located on the Bund side of Suzhou Creek,

since until 1856, the only way to cross the Suzhou Creek was by ferry. Residents

of the British and the American concessions found this inconvenient, and in

response, a British entrepreneur built a wooden bridge, naming it after himself:

Wills Bridge.

But his system of requiring the payment of one copper coin from

the Chinese who crossed the bridge - but letting foreigners cross on credit -

caused a great deal of dissent, and the bridge and its toll system were

eventually dismantled. A floating bridge (operated by the Shanghai Municipal

Council) followed, and in 1906, the steel bridge that the foreigners called the

Garden Bridge (as it ran next to the Shanghai Public Gardens) and the

Shanghainese called "Waibaidu."

That same year, the Astor House Hotel moved

to its current location at the north end of the Garden Bridge, no doubt because

of an unbeatable combination of lower priced land and convenient access. The

following year, three years of construction began on the block-long, lavish

Victorian beauty that has been there ever since. Like its New York namesake, the

new Astor House Hotel became a magnet for the rich, famous and

notorious.

Shanghai historian and author Tess Johnston quotes from a

contemporary description in "The Last Colonies: Western Architecture in China's

Treaty Ports": "The grand staircase, with marble dado and red panels on white

background, leads upward to passenger lifts, a ladies cloak room, a very

prettily furnished ladies' sitting room, a reading room with several comfortable

sofas and easy chairs upholstered in leather, a private buffet with a polished

teakwood bar, and a large billiard room.

"Farther up the grand staircase is

the main dining hall, almost the whole length of the building with a gallery and

verandah on the second floor and well lighted by a barreled ceiling of glass. On

the Astor Road side is a handsome banqueting hall and reception rooms, both

decorated in ivory and gold, and six private dining rooms."

There were six

service elevators, bedrooms with private sitting rooms, and luxury suites under

the dome. An advertisement in Social Shanghai in 1910 bragged, "The Astor House

Hotel is the most central, popular and modern hotel in

Shanghai."

Newspaperman John Benjamin Powell, one of the "Missouri mafia" who

dominated Shanghai's journalism circles in the pre-1949 era, arrived in Shanghai

on a rainy February day in 1917. In those days, boats docked on the Bund, and

Powell recounts in his memoir, "Twenty-five Years in China," negotiating the

treacherously muddy path from the Bund to the haven that was the Astor

House.

He recalls the high society that came here: the American consul

general, bankers, tycoons, all beautifully dressed. And he recalls the words of

an old-timer: "if you look around with open eyes, you will find all the

swindlers who have drifted into this city."

In 1923, the Astor House Hotel

and other Shanghai hotels (including the Palace Hotel) were acquired by Hong

Kong Hotels Ltd, making them Hong Kong and Shanghai Hotels Ltd, a name the

company still carries. The Astor House became a flagship for the newly-formed

company, so much so that even today, a vintage image of the hotel graces the

"history" pages on the company's Website.

Hong Kong and Shanghai Hotels were

owned by the Kadoories, a Sephardic Jewish family that grew to become one of

Shanghai's wealthiest. Born in Baghdad in 1867, Sir Ellis Kadoorie came to

Shanghai in 1880 to work for David Sassoon & Company, the stepping stone for

many Sephardic Jews who arrived in Shanghai, and then went on to make their

fortunes here. Sir Ellis Kadoorie and his sons, Lawrence and Horace, were savvy

businessmen and smart hoteliers, and under their direction, the Astor House

thrived.

As befits a top-class luxury hotel, the Astor House was eager to be

the first in Shanghai with the latest mod cons: the first electric lights,

telephone, talkies, and the first ball, ending the social stricture that women

should not attend social events. Local lore has it that an Astor House bellboy,

rewarded for recovering a Russian guest's wallet with its contents, spent a

third of it on a car. That car became Shanghai's first taxi, and spawned the

Johnson fleet, now known as the Qiangsheng taxi.

Every celebrity who came to

Shanghai stayed at Astor House: in 1920, the philosopher Bertrand Russell; in

1922, Albert Einstein and in 1927, an eight-year-old girl named Peggy Hookham

came to live at the Astor House with her family. Hookham's father was the chief

engineer for British American Tobacco (which was located just over the bridge,

on then Museum Road), and while she was here, the little girl continued her

ballet lessons, studying with the Russian teachers George Goncharev. The world

today knows her as Margot Fonteyn, perhaps the world's greatest ballerina. In

1931, another great artist stayed here: Charlie Chaplin, who liked it so much

that he came back, in 1936, on his honeymoon (they stayed in Room 404, say the

hotel staff).

During the Japanese invasion of Shanghai, the Astor House Hotel

was briefly the Japanese YMCA in 1941, and then rented out for the duration of

the occupation.

The Astor House Hotel struggled along for a few more years.

Renamed the Pujiang Hotel after the Liberation in 1949, it housed the first

stock exchange in modern China. Today, the old Astor House is a favorite

backpacker hotel, the luxury suites and sitting rooms turned into dorms; the

ballroom quiet and neglected. The interior described in Johnston's account is

now gone, but the faded glory is still stubbornly apparent in the details that

remain.