A

statue of Zheng He (Photo: chinanews.com.cn)

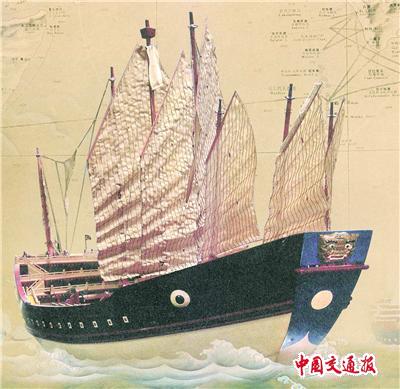

Zheng He's Treasure Fleet

born c. 1371, , K'unming, Yunnan Province, China

died 1435, China

Pinyin Zheng He, original name (Wade¨CGiles romanization) Ma San-pao

admiral and diplomat who helped to extend the Chinese maritime and commercial

influence throughout the regions bordering the Indian Ocean.

Cheng Ho was the son of a ḥ¨ˇjj¨©, a Muslim who had made the pilgrimage to

Mecca. His family claimed descent from an early Mongol governor of Yunnan and a

descendant of King Muhammad of Bukhara. The family name Ma was derived from the

Chinese rendition of Muhammad. In 1381, when he was about 10 years old, Yunnan,

the last Mongol hold in China, was reconquered by Chinese forces led by generals

of the newly established Ming dynasty. The young Ma Ho, as he was then known,

was among the boys who were captured, castrated,and sent into the army as

orderlies. By 1390, when these troops were placed under the command of the

Prince of Yen, Ma Ho had distinguished himself as a junior officer, skilled in

war and diplomacy; he also made influential friends at court.

In 1400 the Prince of Yen revolted against his nephew, the Chien-wen emperor,

taking the throne in 1402. Under the Yung-lo administration (1402¨C24), the

war-devastated economy of China was soon restored. The Ming court then sought to

display its naval power to bring the maritime states of South and Southeast Asia

in line.

For 300 years the Chinese had been extending their power out to sea. An

extensive seaborne commerce developed to meet the taste of the Chinese for

spices and aromatics and the need for raw industrial materials. Chinese

travellers abroad, as well as Indian and Muslim visitors, widened the geographic

horizon of the Chinese. Technological developments in shipbuilding and in the

arts of seafaring reached new heights by the beginning of the Ming.

The Emperor having conferred on Ma Ho, who had become a court eunuch of great

influence, the surname Cheng, he was henceforth known as Cheng Ho. Selected by

the Emperor to be commander in chief of the missions to the ˇ°Western Oceans,ˇ± he

first set sail in 1405, commanding 62 ships and 27,800 men. The fleet visited

Champa (now South Vietnam), Siam, Malacca, and Java; then through the Indian

Ocean to Calicut, Cochin, and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Cheng Ho returned to China

in 1407.

On his second voyage, in 1409, Cheng Ho encountered treachery from King

Alagonakkara of Ceylon. He defeated his forces and took the King back to Nanking

as a captive. In 1411 ChengHo set out on his third voyage. This time, going

beyond the seaports of India, he sailed to Hormuz on the Persian Gulf. On his

return he touched at Samudra, on the northern tip of Sumatra.

On his fourth voyage Cheng Ho left China in 1413. After stopping at the

principal ports of Asia,he proceeded westward from India to Hormuz. A detachment

of the fleet cruised southward down the Arabian coast, visiting Djofar and Aden.

A Chinese mission visited Mecca and continued to Egypt. The fleet visited Brava

and Malindi and almost reached the Mozambique Channel.

On his return to China in 1415, Cheng Ho brought the envoys of more than 30

states of South and Southeast Asia to pay homage to the Chinese emperor.

During Cheng Ho's fifth voyage (1417¨C19), the Ming fleet revisited the

Persian Gulf and the east coast of Africa. A sixth voyage was launched in 1421

to take home the foreign emissaries from China. Again he visited Southeast Asia,

India, Arabia, and Africa. In 1424 the Yung-lo emperor died. In the shift of

policy his successor, the Hung-hsi emperor, suspended naval expeditions abroad.

Cheng Ho was appointed garrison commander in Nanking, with the task of

disbanding his troops.

Cheng Ho's seventh voyage left China in the winter of 1431, visiting the

states of Southeast Asia, the coast of India, the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and

the east coast of Africa. He returned to China in the summer of 1433 and died in

1435.

Cheng Ho was the best known of the Yung-lo emperor's diplomatic agents.

Although some historians see no achievement in the naval expeditions other than

flattering the emperor's vanity, these missions did have the effect of extending

China's political sway over maritime Asia for half a century. Admittedly, they

did not, like similar voyages of European merchant-adventurers, lead to the

establishment of trading empires. Yet, in their wake, Chinese emigration

increased, resulting in Chinese colonization in Southeast Asia and the

accompanying tributary trade, which lasted to the 19th century.

Additional reading

There is no definitive English-language biography of Cheng Ho. The short book

comprising a speech by J.J.L. Duyvendak,

China's Discovery of Africa (1949), is the best general work on the subject

of Chinese naval expeditions of the early Ming; it includes mention of aspects

of Cheng Ho's life in passing.