I Ching

The Book of Changes -- I Ching in Chinese -- is unquestionably one of the most important books in the world's literature. Its origin goes back to mythical antiquity, and it has attracted the attention of the most eminent scholars of China down to the present day. Nearly all that is greatest and most significant in the three thousand years of Chinese cultural history has either taken its inspiration from this book, or has exerted an influence on the interpretation of its text. Therefore it may safely be said that the seasoned wisdom of thousands of years has gone into the making of the I Ching. Small wonder then that both of the two branches of Chinese philosophy, Confucianism and Taoism, have their common roots here. The book sheds new light on many a secret hidden in the often puzzling modes of thought of that mysterious sage, Lao-tse, and of his pupils, as well as on many ideas that appear in the Confucian tradition as axioms, accepted without further examination.

Indeed, not only the philosophy of China but its science and statecraft as well have never ceased to draw from the spring of wisdom in the I Ching, and it is not surprising that this alone, among all the Confucian classics, escaped the great burning of the books under Ch'in Shih Huang Ti. Even the commonplaces of everyday life in China are saturated with its influence. In going through the streets of a Chinese city, one will find, here and there at a street corner, a fortune teller sitting behind a neatly covered table, brush and tablet at hand, ready to draw from the ancient book of wisdom pertinent counsel and information on life's minor perplexities. Not only that, but the very signboards adorning the houses --perpendicular wooden panels done in gold on black lacquer -- are covered with inscriptions whose flowery language again and again recalls thoughts and quotations from the I Ching.

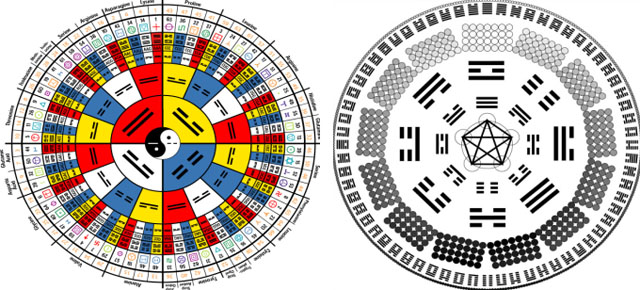

In the course of time, owing to the great repute for wisdom attaching to the Book of Changes, a large body of occult doctrines extraneous to it -- some of them possibly not even Chinese in origin -- have come to be connected with its teachings. The Ch'in and Han dynasties saw the beginning of a formalistic natural philosophy that sought to embrace the entire world of thought in a system of number symbols. Combining a rigorously consistent, dualistic yin-yang doctrine with the doctrine of the "five stages of change" taken from the Book of History, it forced Chinese philosophical thinking more and more into a rigid formalization. Thus increasingly hairsplitting cabalistic speculations came to envelop the Book of Changes in a cloud of mystery, and by forcing everything of the past and of the future into this system of numbers, created for the I Ching the reputation of being a book of unfathomable profundity. These speculations are also to blame for the fact that the seeds of a free Chinese natural science, which undoubtedly existed at the time of Mo Ti and his pupils, were killed, and replaced by a sterile tradition of writing and reading books that was wholly removed from experience. This is the reason why China has for so long presented to Western eyes a picture of hopeless stagnation.

Yet we must not overlook the fact that apart from this mechanistic number mysticism, a living stream of deep human wisdom was constantly flowing through the channel of this book into everyday life, giving to China's great civilization that ripeness of wisdom, distilled through the ages, which we wistfully admire in the remnants of this last truly autochthonous culture.

What is the Book of Changes actually? In order to arrive at an understanding of the book and its teachings, we must first of all boldly strip away the dense overgrowth of interpretations that have read into it all sorts of extraneous ideas. This is equally necessary whether we are dealing with the superstitions and mysteries of old Chinese sorcerers or the no less superstitious theories of modern European scholars who try to interpret all historical cultures in terms of their experience of primitive savages. We must hold here to the fundamental principle that the Book of Changes is to be explained in the light of its own content and of the era to which it belongs. With this the darkness lightens perceptibly and we realize that this book, though a very profound work, does not offer greater difficulties to our understanding than any other book that has come down through a long history from antiquity to our time.

Chuang Tzu

Chuang Tzu is one of the two most prominent primordial texts of what can be called "philosophical Daoism". Its exact relationship with the other basic text, the Laozi, is unclear, though the two texts have a great deal in common. Some scholars have regarded the Chuang Tzu as a commentary on the Laozi, and in some passages this might in fact be the case. But in general the Chuang Tzu has its own philosophical agenda and is unique in many ways. For various reasons, including the Chuang Tzu's apparent reference to passages from the Laozi and the apparent literary sophistication of the former relative to the latter, it seems very likely that the Laozi in some form or another predates the Chuang Tzu.

In some ways it reinvents the Chinese literary language. It makes reference to dozens of stories, myths, and legends common at the time of its authorship, many of which have been lost to us. But the text reworks these stories, eliciting new meanings and significance from them. These references are sometimes rather obscure, which makes reading the text extremely difficult. The text has exerted an extremely powerful influence on subsequent forms of Chinese philosophical thought. This is particularly true of Chan Buddhism and later Daoist thought.

The Chuang Tzu is often described as advocating relativism, and there are certainly relativistic elements to be found. But unlike more thoroughgoing forms of relativism, the text does privilege certain attitudes and behaviors, and thus cannot accurately be dismissed as purely relativistic. At least two different modes of experience are privileged in the text. In terms of mental state, in several places the text advocates a cognitive condition described as ming, or "clarity." Clarity in this case seems to involve the ability to discern subtle distinctions without necessarily evaluating experience in terms of a preferred alternative. Therefore, the text should not be thought of as advocating the obliteration of distinctions in an overwhelming experience of mystical oneness, which is how some commentators and scholars read the text.

In terms of behavior, the text privileges what is called "wu wei" or "effortless action". This kind of behavior seems to involve minimizing conflict with what is inevitable or unavoidable in our experience, and reducing the friction and drag caused by obstinate commitment to a single preferred outcome.

Thus we might draw the conclusion that the ideal person, whom the text variously describes as "genuine" (zhenren), "fully realized" (zhiren), or "spiritual" (shenren), is one who is perfectly well adjusted. That is to say, such a person is balanced and at ease in all kinds of situations, and is not thrown by novelty or unexpected circumstances. An image used by Chuang Tzu to illustrate this kind of adjustment is what he calls the "hinge of Dao" (daoshu). In chapter 2, we find the following claim: "A state in which 'this' and 'that' no longer find their opposites is called the hinge of the Way. When the hinge is fitted in the socket, it can respond endlessly."

Although the presence of privileged modes of experience in the text prevents us from accurately describing it as thoroughly relativistic, still it does seem to be the case that, for Chuang Tzu, all truth and valuation are necessarily contextually situated. This means, for example, that what is good for one individual might not be good for another, and the same goes for beauty, truth, usefulness, and so on. And just as this is the case for different individuals, it is also the case for a single individual at different times.