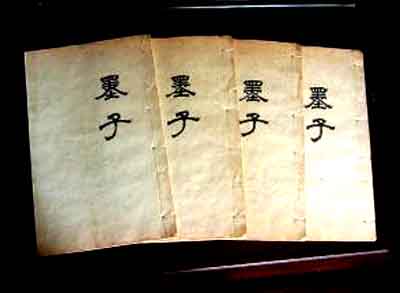

The core Mohist text has a deliberate argumentative style. It uses a balanced symmetry of expression and repetition that aids memorization and enhances effect. Symmetry and repetition are natural stylistic aids for Classical Chinese, which is an extremely analytic language. Three rival accounts of most of the important sections survive in the Mozi.

The "craft theory" of Mohism helps us explain the distinctive character of disciplined philosophical thought in China. As the Mohists analyze moral debates, they turn on which standards we should use to guide our execution of moral instructions. Mozi's orientation was that the standards should be measurement-like, e.g., like a carpenter's plumb line or square. Measurement-like standards lend themselves to reliable application. Experts do better than novices, but everyone can get good results. He tries to extend this reliability-based approach to questions of how to fix the reference of moral terms. Mozi does not think of moral philosophy as a search for the ultimate moral principle. It is the searches for a constant standard of moral interpretation and guidance.

Mozi attacks commonsense traditionalism (Confucianism) as a prelude to his argument for the utility standard. The attack shows that traditionalism is unreliable or inconstant. Mozi told a story of a tribe that killed and ate their first born sons. We cannot, he observeed, accept that this tradition is yimoral or renbenevolent. This illustrates, he argued, the error of treating tradition as a standard for the application of such terms. We need some extra-traditional standard to identify which tradition is right. Which should we make the constant social guide (dao)? For it to give constant guidance, we also need measurement-like standards for applying its terms of moral approval.

Mozi then proposed utility as the appropriate measurement standard for these joint purposes. We use it in selecting among moral traditions, neither directly to choose particular actions nor to formulate rules. The body of moral discourse to promote and encourage is the one that leads to social behavior that maximizes general utility. How did he justify the moral status of utility itself? He argued that it was the natural preference.

Constancy and Nature

The appeal to tian thus becomes an important

component of Mozi's argument. In ancient China, tian was the traditional source

of political authority ("the mandate of heaven"). Early Confucianism had

"naturalized" tian from what many assume was an archaic deity to something more

like "the course of nature." Its main characteristic (besides its moral

authority) was that it's movement was changconstant.

Mozi exploited both the connotations of tian's authority and its constancy. Traditions are variable-they differ in different places and times. If we don't like its traditions, we can flee from a family, a society, even a kingdom. We cannot similarly escape the constancies of nature. Natural constancies thus become plausible candidates to arbitrate between rival traditions. To say a dao was constant functioned a little like saying it was objectively true.

The constant "natural" urge he identified was a comparatively measurable one-we imagine ourselves "weighing" benefits against harms. Thus, he proposed using the preference for benefit as a reliable, natural standard for choosing and interpreting traditional practices. We count as 'moral' and 'benevolent' those traditional discourses that promote utility. The natural urge to utility, he said, is like a compass or a square. It does not depend on a cultivated intuition or indoctrination.