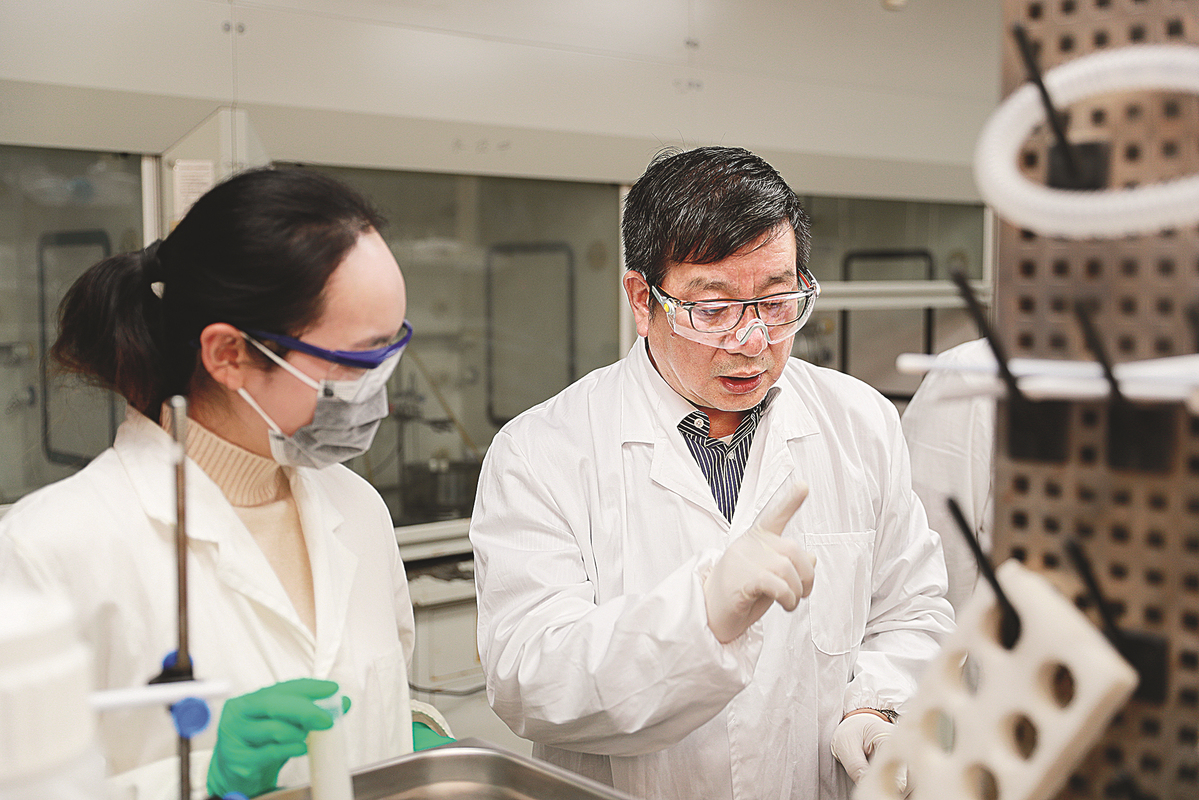

Zhao Dongyuan, a chemistry professor at Shanghai's Fudan University, said that it is still incredible to think that his lifelong passion for "poking holes in materials" could lead to a breakthrough worthy of China's most prestigious prize in basic sciences.

On Wednesday, Zhao and his team took first prize in the 2020 State Natural Science Award. It is the first time Fudan University has won the honor, and the first time in 18 years the award has gone to scientists in Shanghai.

Zhao's work centered on creating a mesoporous polymer and carbon material, a three-dimensional nanostructure with well-defined pores with diameters of between 2 and 50 nanometers. One nanometer is 1 billionth of a meter.

Compared with other microporous materials with pores less than 2 nm in diameter, mesoporous material has higher pore volume and better material transfer efficiency, while compared with macroporous material with pore sizes over 50 nm, it has more surface-active sites, which can lead to increased reaction activity.

Mesoporous materials are widely used as adsorbents and catalysts in oil refineries, medicine, biotech, cosmetics, nanotechnology and other industries.

However, they are typically formed via a self-assembly process that is notoriously difficult to control, hence defects are common during manufacturing.

In 2001, Zhao had an idea. "Mesoporous material up to that point was made from inorganic materials such as silica and metals. So I thought it would be interesting if we could make an organic mesoporous material, which would be softer, lighter and more useful," he said.

Zhao said his inspiration came from his love of poking microscopic holes in materials to see how that changed their properties. "The idea of making organic mesoporous material via self-assembly was almost fantastical, because nobody knew how to do it. We explored all kinds of methods, but to no avail," he said.

The turning point came on Oct 7, 2003. Gu Dong, Zhao's student and now a chemistry professor at Wuhan University in Hubei province, used an unorthodox method of polymerizing the organic molecules first, before assembling them into mesoporous material. The process streamlined the traditional production method and yielded promising results.

Zhao and his team later perfected the method and in 2005, they published their results in the German Chemical Society journal, Angewandte Chemie. Since then, over 1,500 research institutes from more than 60 countries and regions have conducted follow-up studies based on the method.

In China, catalysts made from Zhao's mesoporous material have been used by the Sinopec Group to increase fuel oil production and supercapacitors (a type of energy storage unit) created from the material were used during the 2008 Beijing Olympics and World Expo 2010 Shanghai.

In the civilian sector, Zhao said that he hopes to use it as heat insulation coating for clothes, so that winter garments can be lighter and warmer. It may also be useful for bio-detection, waste treatment, electronics and other industries.

"I love doing research because I get to create new things that didn't exist," he said, adding that it was this passion that propelled him to return home after completing postdoctoral research at the University of California, Santa Barbara in 1998.

At the turn of the century, research conditions in China lagged drastically behind the United States, but this didn't discourage Zhao from studying advanced materials. With a limited budget, he began his work at Fudan University.

Since then, his team has created 19 new mesoporous materials, all named using the university's abbreviation, FDU. Some are produced in amounts of over 1,000 metric tons annually.

On Jan 9, Fudan University and the National Natural Science Foundation of China opened a new science center dedicated to basic research in mesoporous material on the campus.

"The center will focus on making more world-class breakthroughs, and create a new generation of catalytic materials named after Chinese scientists and institutions," Zhao said. "I hope more and more Chinese names will be found in science textbooks in future generations."