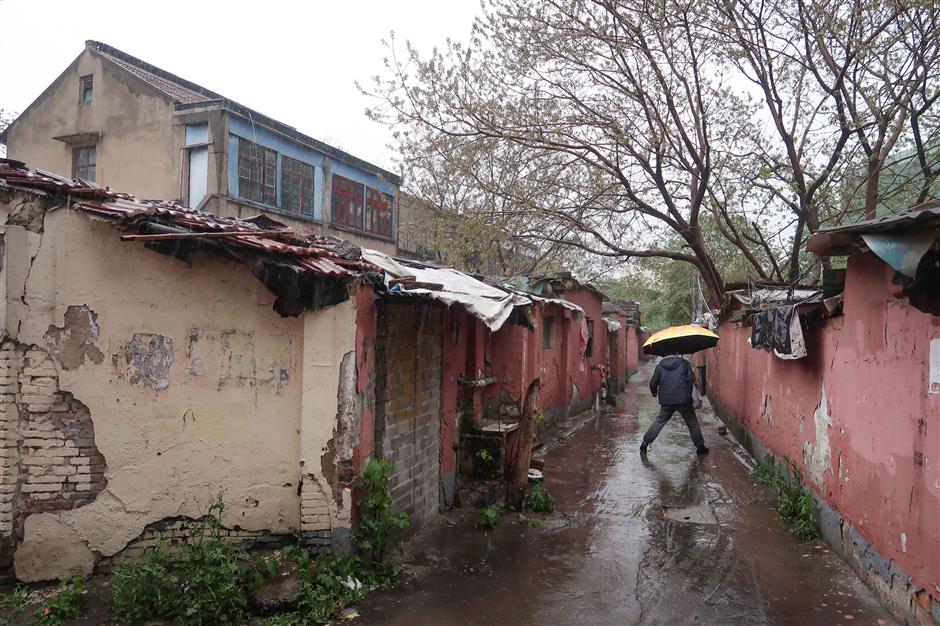

Zhayin Village was once a rural backwater where farmers tilled land. But rapid urban development gobbled up the farmland and encircled the village with high-rise buildings. The living environment for the more than 1,000 residents worsened by the year, turning the area into an urban eyesore.

Wang Rongjiang / SHINE

Wang Rongjiang / SHINEAn electronic board at the gate of Zhayin Village keeps a tally on the number of residents who have agreed to relocate under the government’s urban redevelopment plan. The government is paying them cash subsidies. The earlier people sign up, the higher the subsidy.

URBAN village. It’s a contradiction in terms that’s being bulldozed out of government lexicon.

Zhayin is the last officially designated “urban village” in Yangpu District, though it hardly looks like the stereotyped image of a quiet, idyllic spot. In fact, it’s a shantytown sitting in the shadows of skyscrapers, and it’s soon to be demolished.

Wu Xiaodi, 60, the Party secretary of the Shiguang neighborhood committee that has Zhayin under its jurisdiction, isn’t mourning its passing. He said he has long feared for the welfare of the more than 1,000 residents, most of whom were attracted to the village by its low rents.

“I can barely sleep at night every summer and winter for fear that the low-lying village might be flooded or that roofs will collapse under heavy snow,” Wu said.

“I’m happy for the villagers. Some of them are living in crammed quarters with no separate toilets or piped gas for cooking. With the demolition, they will be relocated to a better lifestyle.”

Beginning in 2014, the Shanghai government initiated an urban redevelopment program for 35 “urban villages” like Zhayin, under guidelines issued by the State Council, the nation’s cabinet, to eliminate shantytowns.

“It is a natural process for these villages to disappear in the wake of modern urbanization,” said Xue Liyong, a local historian and a senior researcher at Shanghai History Museum.

In the case of Zhayin Village, the government is paying cash subsidies to the owners of 354 parcels of land. Nearly all residents have agreed to relocate — most with great relish.

Once everyone is gone, bulldozers will begin tearing down the village, which is located near heavily trafficked Shiguang Road and is 2 kilometers from the bustling Wujiaochang commercial hub.

SHINE

SHINEZhayin Village is located near heavily trafficked Shiguang Road and is 2 kilometers from the bustling Wujiaochang commercial hub in Yangpu District.

Urban redevelopment plans for the site haven’t been unveiled yet. When demolition of the “urban village” of Hongqi in Putuo District was completed last year, the area was turned into a greenbelt.

Zhayin Village came into being more than a half century ago as a home for farmers working surrounding farmland. It was once a beautiful rural watertown, with stone bridges crossing a small river, said Wu.

Under rapid urban development that began in the 1990s, the farmland disappeared and high-rise commercial buildings began encroaching on the village. Accommodation became increasingly cramped, along with a worsening environment.

About 10,000 square meters of residential buildings, mostly wood-and-brick structures built by the villagers, comprise the 8 remaining hectares of the village.

Most of the original residents have long gone, renting out their properties to migrants at a maximum of 500 yuan (US$79) a month, far cheaper than most other properties in Shanghai’s downtown area.

In spite of stabs at rehabilitation initiated by the township and district governments over the years, the village never escaped from impoverishment. Its streets are so narrow that two people can barely walk on them side by side. Motorcycles whiz past, and the air is foul because of piles of garbage strewn about.

To address a shortage of living space, residents attached illegal structures to their homes. They still use gas cylinders, which pose fire risks.

During the plum rain season every summer, parts of the village are inundated by knee-deep water due to poor drainage and low-lying terrain. Wu has had to relocate some inhabitants to the auditorium of a nearby elementary school in cases of emergency.

He still recalls three years ago, when a two-story building in the village collapsed after a gas explosion and five residents were buried in the rubble. Fortunately, they were pulled to safety by firefighters.

Then there was the accident two years ago when faulty electrical wires installed by tenants caused a fire that engulfed a house.

Again, there were no casualties.

But the village has remained an accident waiting to happen.

“Since then, I have often patrolled the village to try to identify safety risks,” Wu said.

He walks to his office every day in galoshes to navigate the muddy pathways. He knows the whole maze of village lanes and everyone living along them.

Wang Rongjiang / SHINE

Wang Rongjiang / SHINEIllegal power lines wind under the roof of a shanty building in Zhayin Village. Two years ago, faulty electrical wires installed by tenants caused a fire that engulfed a house. Luckily there were no casualties.

Wang Rongjiang / SHINE

Wang Rongjiang / SHINEWu Xiaodi, 60, the Party secretary of the Shiguang neighborhood committee that has Zhayin under its jurisdiction, said he is happy that the residents will be relocated to a better lifestyle.

Illegal structures

In 2016, the Wujiaochang Township government launched a crackdown on illegal structures as part of a citywide campaign. Over 15,000 square meters of illegal, jerrybuilt structures were torn down, but that didn’t do much to improve the living environment, Wu said.

“It just seems to get worse after each government effort to improve the environment,” said Hu Yuanhui, deputy director with the Wujiaochang government. “It has been a great burden on the town government.”

The family of Chen Boliang is among the few original settlers still remaining in the village. More than 80 percent of Chen’s neighbors are out-of-towners, mainly migrant workers from the provinces of Anhui, Jiangsu, Hunan and Jiangxi.

Eight family members, including Chen’s wife, two sons and grandchildren, squeeze into two 25-square-meter houses near the east entrance to the village. Chen added a story to each houses in the 1990s, with the permission of officials then in charge of the village.

Wang Rongjiang / SHINE

Wang Rongjiang / SHINEThe low-lying village is subject to flooding during the rainy season due to poor drainage system. Residents sometimes have to be evacuated to emergency shelters until the floodwaters subside.

Wang Rongjiang / SHINE

Wang Rongjiang / SHINEResident Chen Boliang, 60, has old emotional ties to the village but he admits it’s not a good place to live anymore. Eight members of his family will share the 17.5 million yuan (US$2.7 million) relocation subsidy, but Chen says the money won’t go far in a city of sky-high housing costs.

“I have been emotionally bound to the village because I spent more than four decades of my life here,” the 60-year-old Chen told Shanghai Daily. “But I want to improve the living condition of my family.”

His family will receive a subsidy of 17.5 million yuan for relocation, but Chen said the money won’t go far in finding new quarters for a large family in a city of skyrocketing housing prices.

Disputes about how to share the cash has caused family friction, he said.

“I plan to move to Chongming Island, where I can raise pigeons,” Chen said. “Housing is more affordable there.”

Chen’s neighbor Yuan Hengqing said he had been dreaming for decades about moving from his birthplace.

“I signed the relocation contract as soon as I was approached by government officials,” he said.

“I hope I will receive the money soon so I can get away from this place.”

In fact, half of the property owners quickly put their names on the dotted line on the first day the relocation process began. They have a choice: move to designated housing on the outskirts of the city or purchase properties on their own.

Some 96 percent of residents have signed relocation papers. The earlier people sign up, the more subsidy they receive.

“Many residents have promised to invite me to visit their new homes,” Wu said. “I’m looking forward to seeing their new lifestyles.”