Editor’s note: This year, we are releasing a new series of stories themed on “Red Finance: CPC’s Financial History in Shanghai”. Here is an article about Zhang Renya, a pioneer of Shanghai’s gold and silver industry labor movement.

A special cenotaph sits on a hill near Xianan Village in Beilun, Ningbo, Zhejiang Province. 94 years ago, a cohort of CPC documents and Marxist literature were secretly hidden in the cenotaph. Among them is one of the earliest Chinese editions of the Communist Manifesto. Its protector was Zhang Renya, a CPC member who was also a pioneer of Shanghai’s gold and silver industry labor movement.

(A statue of Zhang Renya near his cenotaph)

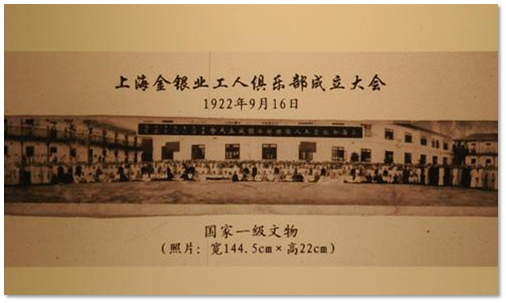

We paid a visit to Xianan Village, Zhang’s hometown. A big group photo in his former residence caught our attention. With a length of 1.44 meters, it is a replica of a first-class national cultural relic currently housed in the memorial hall for the first National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in Shanghai.

(A group photo of the Shanghai Gold and Silver Industry Workers’ Club taken on September 16, 1922)

Zhang, wearing a white jacket, sits in the center of the photo, taken on September 16, 1922, the day when the Shanghai Gold and Silver Industry Workers’ Club was officially founded. At the founding meeting of the Club, 24-year-old Zhang spoke as club president to all the participating workers, saying that the Club would“eliminate all misfortunes and improve our lives in the future.” Standing on the podium, he made a passionate speech, calling for workers to rebel against oppression.

(Zhang’s former residence in Xianan Village)

Zhang was born in 1898 into a poor family. At 16 years old, he had to drop out of school and went to Shanghai to make a living. He apprenticed at a Lao Feng Xiang silver shop in Shanghai. Never giving up on studying, he went to a night school in 1921, the year when the CPC was founded.

It was in Shanghai that the aspirational youth became acquainted with many revolutionary activists. In 1922, Zhang became a member of the China Communist Youth League (which was then called the Shanghai Communist Youth League) and later joined the CPC, making himself one of the few worker CPC members in Shanghai.

(Zhang Renya)

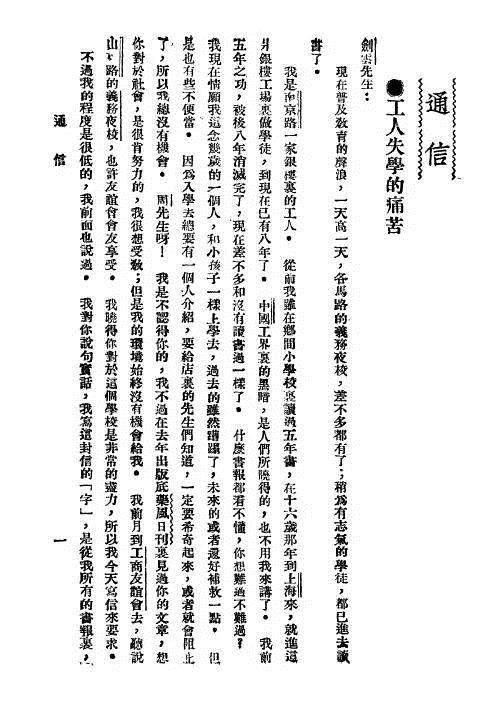

In a letter he wrote to Zhou Jianyun, chief editor of Liberation Pictorial (the 1st pictorial in the history of Chinese women's newspapers and periodicals), Zhang mentioned why he’d like to become educated--because of the darkness of the Chinese industrial circle at that time. “Apprentices who have aspiration all go to school. I’d like to go to school too, even at this age. My past was wasted. Now I want to make some remedy maybe for my future,” he wrote.

In the 1920s, there were 34 silver shops in Shanghai, but the workers were badly treated and led a poor life. Fully aware of the conditions of the workers, and influenced by new thoughts and cultures, Zhang soon became a leader in the labor movement in the gold and silver industry.

The Club was the Shanghai Gold and Silver Industry Workers’ Club and was set up with the support of the Chinese Trade Union Secretariat under CPC leadership. More than 1,600 people joined the Club. Less than one month after the Club’s establishment, Zhang, director of the club, led a strike in Shanghai in October 1922, which lasted 28 days. At last, the capitalists compromised and agreed to pay the workers during the strike and improve their working conditions. Alongside six worker representatives, Zhang signed an agreement with the capitalists, thus protecting the workers’ interests.

That was the longest strike held in a city since the CPC was founded. Since then, Zhang embarked on a path of revolution.

Story by Zhang Haiying, Liu Li, Liu Hao, Wang Weiqiu, Chao Siyuan

Translated by Wu Qiong